Since the publication of our last blog post, the Shaping Scholarship team at UCL’s Centre for Editing Lives and Letters has been busy continuing our important research into early donations to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Our post-doctoral research associate Anna Lujz Gilbert has spent the past few months at the University of Oxford, examining hundreds of valuable rare books to establish which titles gifted to the library survive amongst the Bodleian’s thirteen million printed items. I’ve also joined the team as a research associate. When I’ve not been working on my DPhil (PhD) in English literature and women’s book history c.1550-1760 at the University of Oxford, I’ve been completing the Institute of Historical Research’s excellent course in database design and getting up to speed with the project’s progress. A key part of this has been getting to grips with Shaping Scholarship’s foundational document and the subject of this blog post: the first volume of Donor Register used to record the thousands of gifts to the library between 1602 and 1688.

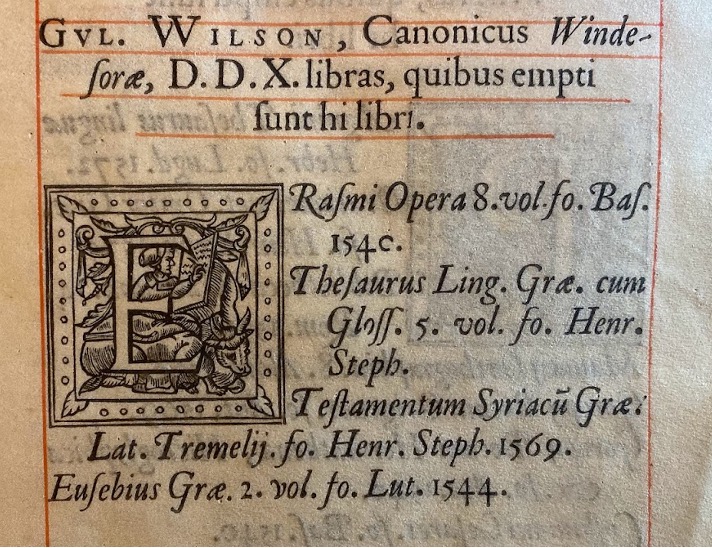

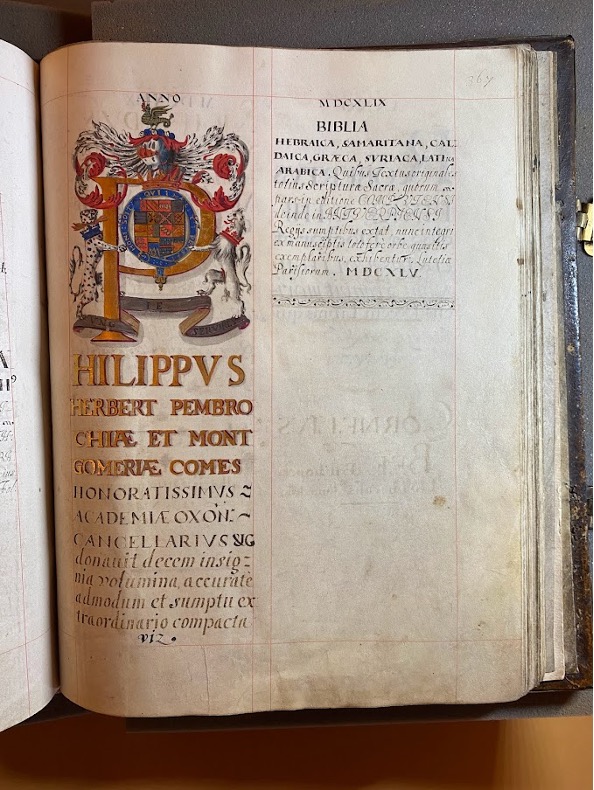

Plans for a donor register began long before the library officially reopened its doors in 1602. An experienced and aspirational Elizabethan courtier who spent decades navigating the corridors of power as a continental diplomat, Sir Thomas Bodley understood the significance of properly recognising the contributions of benefactors. From 1601 onwards, he instructed the first librarian Thomas James that ‘any offers of gifts’ of money, books, objects ‘no matter how informal, … shall be heereafter publikly registered’ alongside the donor’s names and titles in scholarly Latin. In 1604, the king’s printer Robert Barker transformed James’s manuscript index of donors, which included important figures such as the coloniser Sir Walter Raleigh and Elizabeth I’s favourite the Earl of Essex Robert Devereux, into the hefty volume organised by social rank we see today. Initially printed on luxurious thick vellum, prepared animal skin, entries from 1605 onwards were continued in manuscript by a succession of scribes, allowing for the addition of beautifully illuminated initials in precious pigments, such as that recording the Earl of Pembroke Philip Herbert’s donation in 1649. Masterminded by one of the original social influencers, donating to the Bodleian and having your name recorded in the register ‘quickly became associated with honour and prestige’.1 As Thomas Barlow remarked in a letter thanking the diarist John Evelyn for a gift of books in 1654/5, having your name inscribed into the ‘Register, amongst those noble and publique soules which have beene our best Benefactors… will be noe dishonor to you, when posterity shall there read your name, and charity’.2

Image 1: An example printed entry for William Wilson, Canon of Windsor, who donated four books in 1600. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903, p.21

Image 2: The Earl of Pembroke Philip Herbert’s richly decorated entry in the register recording his donation made in 1649. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903, p.367.

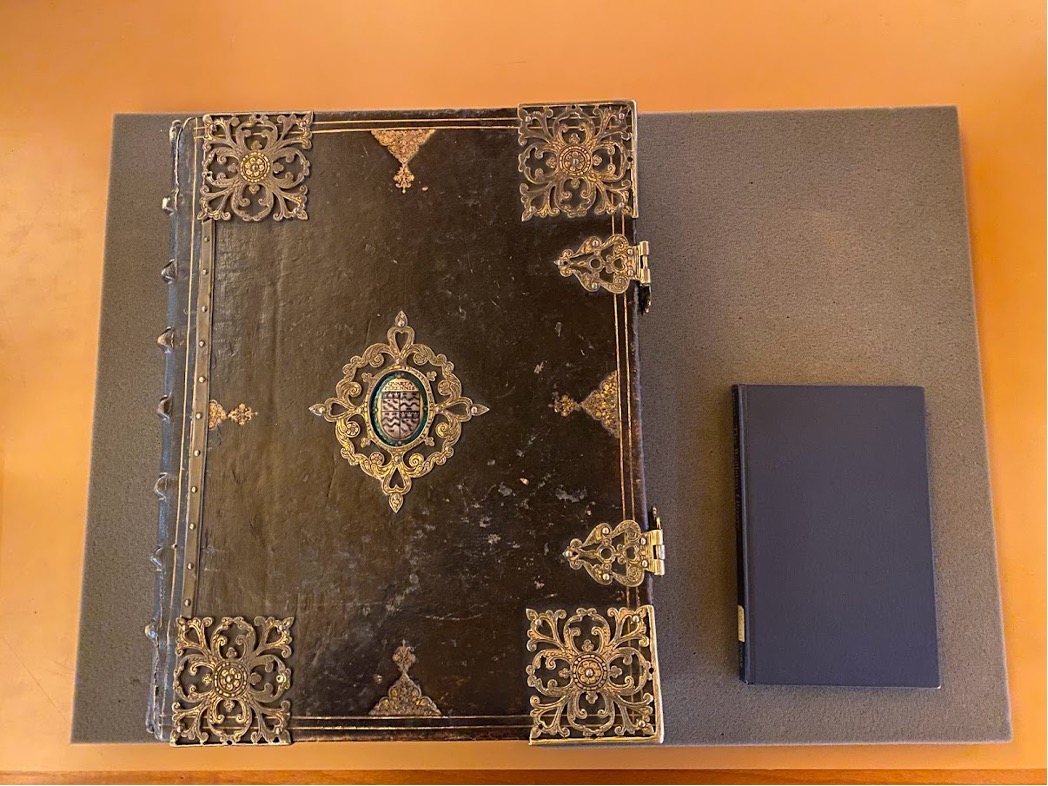

Referred to by Bodley as ‘my publike register’, this book was designed to be seen, impress, and encourage further donations.3 Bound in heavy wooden boards covered in fine leather, adorned with engraved metal furniture, fastened by silver clasps, and unusually embellished with an enamelled central boss depicting Bodley and Oxford University’s combined coat of arms, the register is an impressive object and was an unmissable material presence in the early Bodleian. With a height the quarter of the average UK male and weighing 10.5kgs, the equivalent of two large cats or one small king penguin, this tome could not be easily moved or read in your lap as we think of doing with your average book today. Bodley stipulated that it be chained to a specially constructed desk. This safeguarded the valuable tome and enabled it to remain on constant display to visitors well into the twentieth century, as well as allowing keepers of the library to show visiting donors their names inscribed amongst those of the scholarly great and good.

Image 3: Our glamourous CELL cat models weigh as much as the register. Fabulous ear hair not included in calculations. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903. Royalty-free scale image from Shutterstock.com

Image 4: The register is around four times the size of the average modern book. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903.

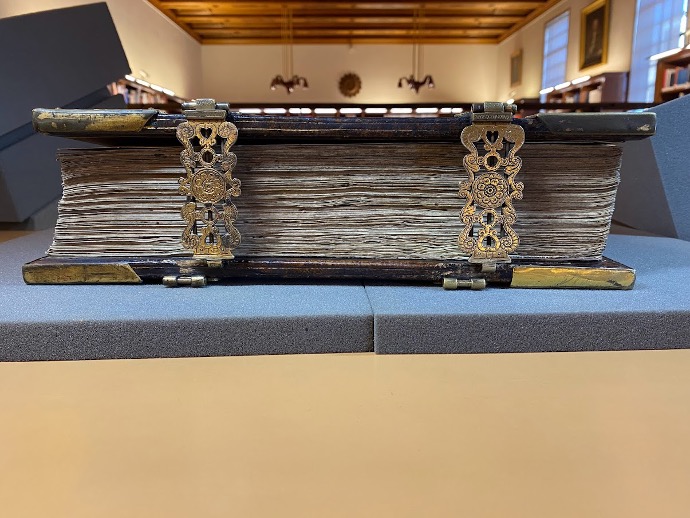

Marks of use left behind by these visitors and scribes attest to the register’s long life of being constantly read, updated, and handled. Touch has softened the sharp edges of the copper furniture. Frequent page turning has smoothed the corners of the velvet-textured vellum, the natural oils from readers fingers even blackening the pearly-white surface in some places. Scribes and their clumsy elbows similarly contributed to this mess-en-page when updating the volume through their occasional splatters of spilt ink. The original spine has also long since been replaced, having eventually given way having successfully borne the weight of several cats for centuries every time the volume was opened. A testament to the sheer amount this book was used can be seen in the scarred silver clasps that keep the volume closed. The library’s early account book records that they had to be repaired and regilded a whopping six times between 1629-42 by Mr Berrie the goldsmith, eager readers having broken the terminals and rubbed away their glittering surfaces.4

Image 5: Coming in with a thickness of 11.5cm, the register is one chonky tome. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903.

Image 6: If you look closely at the volume’s gilded clasp, you can see where Berrie the goldsmith has soldered a piece of metal to repair one of the many breaks. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903.

Image 7: Example of one of the worn and blackened vellum corners in the benefactors register. Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903, fol.1r

The donor’s register is a rich, complex, and influential document. Bodley’s volume set a trend for other academic institutions that continued for centuries, and is vital to understanding how practises of donation shaped subsequent scholarship in one of the world’s largest libraries. But at times it is also rather tricksy. Despite purporting to record all donations, in 1602 the sheer volume of gifts and bookish snobbery led Bodley to instruct James that if he received ‘a very poore gifte’, i.e. one of low monetary or intellectual value, ‘we may not fille up the Register with such benefactours’.5 This revelation raises a series of questions. What works were considered ‘poor’? Whose donations and what social groups were excluded from the milieu created within the register? And how do you go about tracing non-register donations in a collection containing thirteen million printed books? These are just a few of the questions we hope to answer as our project continues.

1 Thomas Bodley, Letters of Sir Thomas Bodley to Thomas James, First Keeper of the Bodleian Library, ed. G. W. Wheeler (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1926).

2https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11288/lot/343/. [Accessed 11.1.23]

3Letters of Sir Thomas Bodley to Thomas James, p.82.

4The Bodleian Library Account Book, 1613-1646, ed. Gwen Hampshire and I. G. Philip (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1983).

5Letters of Sir Thomas Bodley to Thomas James, p.42.

Related Posts

- Introducing the Shaping Scholarship Project

- Shaping Scholarship: Early Donations to the Bodleian Library

Follow us on Twitter @ShapingScholar

For more on this topic your might like to read:

- Robyn Adams & Louisiane Ferlier, ‘Building a Library Without Walls: the Early Records of the Bodleian Library’ in Libraries, Books & Collectors of Texts, 1660-1800, ed. A Bautz & J Gregory (Routledge, 2017)

- William Poole, ‘Collection by Donation: the Benefactors’ Registers of Oxford College Libraries in the seventeenth century’ in Book Collecting in Ireland and Britain: 1650-1850, ed. Elisabethanne Boran (Four Courts: Dublin, 2018)

Header image: Donors register front board, Bodleian Library, Library Records b. 903